Thermoregulation Basics in CrossFit Athletes

By Sean Rule

*Disclaimer: I’m not a doctor, this isn’t medical advice, consult your Primary Care Physician before trying any of this.

Hey TCFers! It’s getting to be that time of year when each and every CrossFit class throughout the day is heating up, not just in intensity, but in temperature too. As coaches, we do our best to be efficient in the hour you give us, and hopefully that includes cool down time after the WOD. But, we understand, you guys have lives; places to go, things to get done!

Let’s break down the “cool down” portion of the workout. First things first, keep moving! It feels great to collapse on the ground after you’ve put your all into the workout, but next time, try to get back up relatively quickly and keep moving. Cheer on those who haven’t finished, and put your equipment away once everyone’s done. If you have time, take a walk, or get on the bike with the rest of the class post workout.

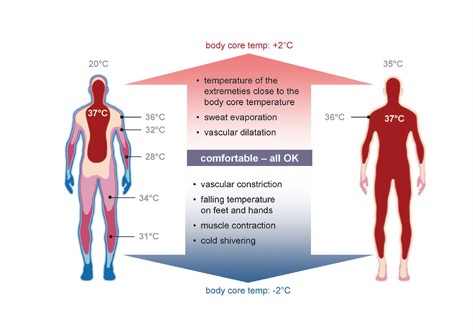

And what are we talking about when we mention thermoregulation? The best definition I found was from the University of Connecticut:

“Thermoregulation is the body’s natural cooling system. Central nervous system sensors measure the body temperature and send a signal to the hypothalamus if it changes. The hypothalamus activates hormones and body mechanisms designed to bring the core temperature back into check. This is what keeps organisms like human beings at homeostasis, or at a stable core temperature, regardless of the environment. Whether it is 35° or 120° outside, your body strives to maintain a core temperature close to 98.6° Fahrenheit.

Thermoregulation works within a very narrow window. Any shift in temperature can cause a physical reaction. When you sit in a hot car, your temperature rises just a couple degrees before you start sweating. That is the body’s attempt to bring your temperature back down. Conversely, if you go out into the cold and your temperature drops a degree or two, you begin to shiver. This movement generates energy that warms you back up. The shivering stops when you are once again in a state of homeostasis.”[1]

Continuing to move after the workout keeps the blood flowing, removing metabolic waste products from the muscle and reducing soreness. In addition to assisting athletic recovery, these actions also promote more efficient thermoregulation. Active, and even passive recovery techniques have been shown to be more beneficial for proper thermoregulation than inactive recovery.[2] Active recovery is the stuff we’ve already mentioned, stretching, biking, walking, with a purpose after you’ve exerted yourself. While passive recovery includes the use of compression devices, electrical stimulation, or massage. The inactive recovery they tested these techniques against in the study was sitting upright on a bike seat, equivalent to sitting in your car.

Let’s put this into context at the gym. You’ve just finished the workout, your brilliant coaches planned it so that everyone would have completed the WOD five minutes before the top of the hour (or you have an extra five minutes). At this point, you are in a transition period, where you can either continue the process of down regulation for maximal benefit or be on your way if you’re in a rush. As your heart rate begins to get closer to normal, consider getting into a seated position against the wall. If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is the same position as the low back release we encourage after especially taxing workouts.

This is the best example of Lower Body Positive Pressure (LBPP) we can provide without compression chambers or a device like the Normatec leg sleeves. LBPP has been shown to be an effective way to lower core temperature after a bout of exercise.[3] An additional way to get some LBPP would be to be seated upright, back against the wall, legs directly out in front, with a plate of at least 25lbs held like a steering wheel, rolling side to side, up the quadriceps from the top of the knee. If you can continue breathing at a consistent, relaxed rate, foam rolling the calves, hamstrings and quadriceps can be an effective method as well.

Remember that every body is different, so experiment (safely) with these techniques to find what works best for you.

Add an ice pack for further down regulation, after a few minutes of this, lying down and breathing (see link below)

Things to try:

Continue moving for a few minutes after everyone is finished, take a walk or bike before you hop in the car!

Apply an ice pack or cool towel to your neck, armpits, forearms or thighs for a few minutes[4] while on the bike or in the low back release position up against the wall. These modalities are the closest thing we have to cold water immersion or ice baths at the gym.

For better breathing technique, I recommend you check out this instructional piece and video from Barbell Shrugged and SealFit’s Mark Divine.

http://daily.barbellshrugged.com/breathing-meditation-techniquewod/

References

- Journeay WS, Reardon FD, Jean-Gilles S, Martin CR, Kenny GP. Lower body positive and negative pressure alter thermal and hemodynamic responses after exercise. Aviat Space Environ Med 75: 841–849, 2004.

- Glen P. Kenny, Daniel Gagnon. Is there evidence for nonthermal modulation of whole body heat loss during intermittent exercise?

American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology Jul 2010, 299 (1) R119-R128; DOI: 10.1152/ajpregu.00102.2010 - http://ksi.uconn.edu/2015/05/17/how-thermoregulation-can-give-athletes-an-edge-mission-athletecare/

- Casa DJ1, McDermott BP, Lee EC, Yeargin SW, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. Cold water immersion: the gold standard for exertional heatstroke treatment. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007 Jul;35(3):141-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17620933

[1] http://ksi.uconn.edu/2015/05/17/how-thermoregulation-can-give-athletes-an-edge-mission-athletecare/

[2] Glen P. Kenny, Daniel Gagnon. Is there evidence for nonthermal modulation of whole body heat loss during intermittent exercise?

American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology Jul 2010, 299 (1) R119-R128; DOI: 10.1152/ajpregu.00102.2010

[3] Journeay WS, Reardon FD, Jean-Gilles S, Martin CR, Kenny GP. Lower body positive and negative pressure alter thermal and hemodynamic responses after exercise. Aviat Space Environ Med 75: 841–849, 2004.

[4] Casa DJ1, McDermott BP, Lee EC, Yeargin SW, Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. Cold water immersion: the gold standard for exertional heatstroke treatment. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2007 Jul;35(3):141-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17620933